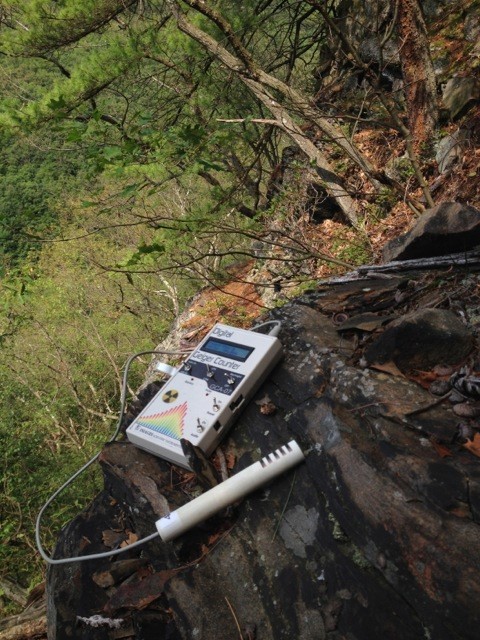

One thing I was certain of was that if I didn't get myself out of the path of these searing ions, my adventure would be cut short. I would unfortunately have a hard time hiking myself out of this remote and rugged location. I longed to get back down to the cool forest floor and the welcome relief of the canopies shade. I had been cooking in the hot sun on this exposed cliff side for too long at this point. Hours earlier, I sat and waited patiently as the sun rose over the upper grand section of the Lehigh Gorge, burning away the clouds—which obscured the view of the valley below and its hidden geology. From our vantage point nearly a thousand feet above, the roaring whitewater rapids were little more than a dull roar, lost to the wind.

Several hours after the first light had crept upon the horizon, we were finally granted the birds eye view we had been waiting for. In that valley down below, just out of sight around the bend, was a legendary local I had spent many hours researching. I was determined to finally unravel the lost secrets of this complex and unique Uranium deposit. This process started many millions of years ago when this solid ground upon which we stood was merely sediment settling upon the ancient seafloor. Through complex geological developments, Uranium and its secondary minerals—such as carnotite, autunite, tyuyamunite, uranophane, and kasolite—would be concentrated in the sandstone. The sandstone would eventually rise above the waters of the sea, only to be cut through by the persistent flowing river that carved out this deep and nearly impenetrable Gorge.

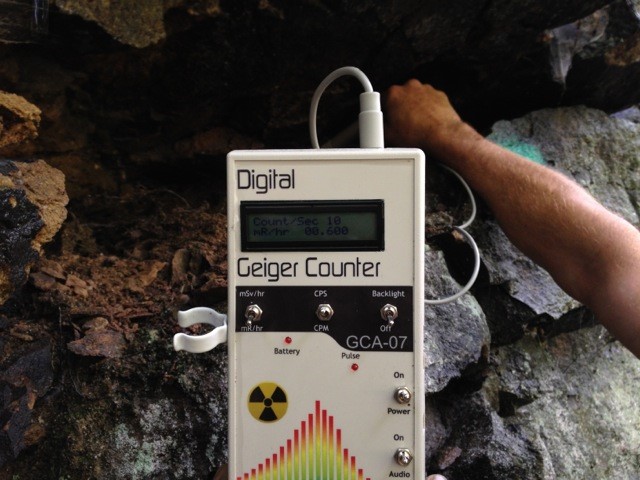

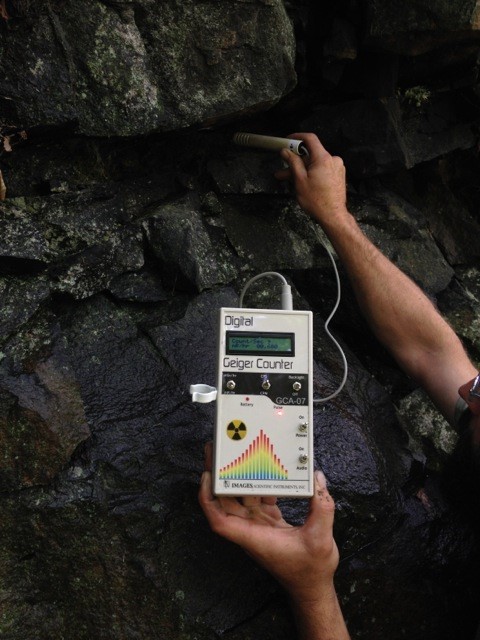

Known as the most remote and uninhabited corner of Carbon County, this Gorge is steeped in a rich history. For example, the Gorge is involved in the discovery of anthracite coal here and in neighboring Lackawanna County. The discovery led to the subsequent development of a system of locks and gravity railroads, which were used to transport the coal down river to Philadelphia. Previously, my only option for prospecting these radioactive minerals was the Botanical method of prospecting. This involves analyzing growth patterns in the local fauna and looking for mutations, which could indicate high levels of radioactivity. Now, however, I was armed with the IMAGES Co. GCA-07W model Geiger counter: a reliable and accurate unit with a separate wand, which would allow me to dive right into the dirty underworld of uranium prospecting. My safety against bombardment by excessive ions was assured, as was the possibility of tracing those ions to their source, rare radioactive minerals.

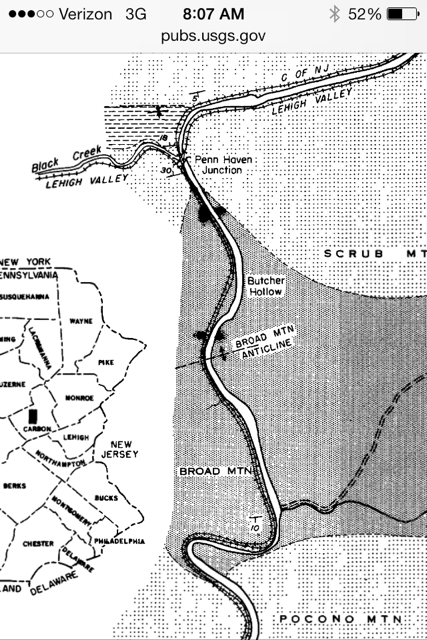

The discovery of Autunite by Dr. Bertine Erwin in 1874 led to the geological exploration of the Lehigh Gorge. The climax of this exploration would be seen in the 1950s; the onset of the Cold War drove the need to develop domestic supplies of Uranium in order to maintain a nuclear edge. In my pack I had the Geiger counter, a couple bottles of water, a safety rope, some carabineers, a climbing harness, a headlamp and some extra batteries. I also had a map noting the locations of the original uranium prospects from US Geological Survey Bulletin 1138. It was merely a crude black and white map, which would only get me to the general area; I would need to use the wand equipped Geiger counter to pinpoint the actual hotspots.

I had chosen the most remote of the dozen or so separate prospects for this adventure. It required a five-mile hike, complete with a river crossing, rugged terrain, steep gorges with loose rock and rushing streams, all of which offered unique challenges to navigate. To me, the journey was well worth it to access the picturesque abandoned railroad grade. The site was also overgrown with vegetation-some of which I was eager to come upon-such as the ripe raspberries and blackberries growing at the base of the cliff. I knew to stay away from others, namely the poison ivy and poison sumac common in this deciduous forest. I knew it was likely I could locate the radioactivity at the other sites, but they were located on property owned by the railroad and I didn't want to trespass without permission. Beside, this was my idea of a good time. Bushwhacking my way at times, carefully edging along sparsely vegetated weather worn drop-offs, and clinging to massive grapevines as I navigated loose rock-slides, I made my way slowly and carefully. I removed the Geiger counter from my pack systematically to analyze the rock upon which I tread. I had chosen this route by looking at topographical maps. I assumed that in the steepest areas of the stream carved gorges I would find a large majority of the areas exposed rock, most importantly, accompanied by abrupt change in elevation which would give me opportunity to intersect the exposed layers of the Catskill formation. I couldn't detect any visible change in the geology of the exposed Cliff side rock, but the Geiger counter had no problem locating the uranium-bearing layers. As I descended in elevation, I finally came upon the abandoned railroad grade. It had been many years since a train had run along this line. Huge oak and maple trees created a thick canopy, dotted here and there by the rays of the hot summer sun. The cliff was seeping water everywhere-this was the summer rainy season. The flood of 1888, brought on by days of torrential downpour, occurred in this Gorge. The flood burst the dams and locks that were Josiah White's unmatched engineering marvel, creating a domino effect that took the lives of more than 200 men. I couldn't help but think about how many of those men had drank unknowingly from these same springs issuing forth from the Cliff side, unaware of the dangers posed by the long-term exposure to radiation. I brought my own water. I had climbed down from the perilous cliff side to the flat grade. I kept the Geiger counter out and turned on, checking any exposed rock in my path. I still wasn't getting the readings I expected, just a slightly elevated reading here and there, not much more than background radiation. Suddenly, it spiked!

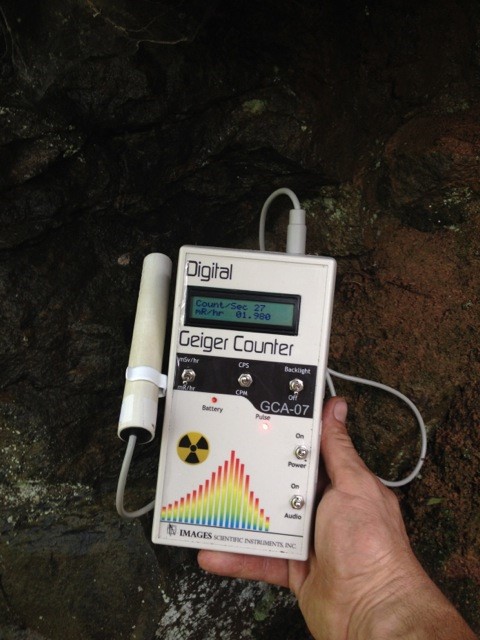

I was checking the base of a large boulder which had fallen from the cliff side many years ago when I got a high reading, which I quickly realized was actually coming from the ground below. Not wanting to exfoliate the plants at the base of the rock, I looked up and did a visual scan of the perimeter for a likely source. I saw it: the telltale green spray paint marking on the cliff side which had originally been put there more than 50 years ago by geologists Harry Klemic and R. C. Baker when they first discovered this deposit. As I approached the exposed rock the readings spiked, I was still 15 feet from the cliff when the Geiger counter’s bleeps started coming closer and closer together. I will never forget the rush I felt in that first moment as I closed the distance to the cliff side and the bleeps grew to be so fast that they became one long ear splitting ring. This was it! The Geiger counter was going off like crazy! The only time I had heard it do this before was when I had tested it out a week earlier at the Gilsum New Hampshire Rock and Mineral show. I had gotten some high readings examining autunite crystals, which had been collected many years ago at a quarry in Maine. This was totally different. I was very woods where I had grown up, surrounded by the familiar terrain, but now seeing in a completely different light. I would never look at this rock the same way again.

I spent some time examining the various test audits at the base of the cliff, making note of the areas where I got high readings, and being careful not to disturb the crumbling rock. I could spend all day examining this fascinating mineralogical wonder, but the sun was waning in the sky and I had a long hike out. I packed up my knapsack, took some pictures, and left nothing but my footprints in the soft mud as evidence of my thrilling discovery. As I started up the trail I couldn't help but daydream of what it looked like here 62 years ago when Harry Klemic and R. C. Baker walked this same path out. I am sure my excitement was unparalleled by theirs upon first discovering this unique geological deposit, but for me the satisfaction was just the same.